In 1964, she published Other People’s Houses, an autobiographical novel about a young girl named Lore who spends seven years in foster care with families along the entire spectrum of the English class system. It is the story of refugees, newly relevant as a tide of anti-migrant sentiment and anti-Semitism surges in the west.

“I’m not surprised by anti-Semitism when it rises again,” she says. “This [has been] an interim. A fortunate interim, in my head. I’m especially appalled to think about the unaccompanied children who are travelling through the world right now.”

Her story is different from those of the children being separated from their families by American authorities at the US-Mexico border or crossing the Mediterranean or Sahara. But she understands the mindset. “I think refugees are never mentally entirely safe . . . This is hardly my own thing. Many people go through many experiences, and there’s some of us who know that when the gun points at you, it goes off.”

In the book, Segal writes about the first Nazi regiment arriving in Vienna. The family’s yard had been requisitioned as the paymaster’s headquarters. Her parents told her to stay out of the way, but she was a child — she wanted to be seen by these grey-green-suited strangers. So she mildly tormented her cat until it yowled and the paymaster finally took notice. “He asked me if I knew how to skip rope, and I said yes. He ordered one of the helmeted guards to hold the other end of the rope. The line of soldiers stood at ease against the vine-covered walls. I skipped and recited, ‘Auf der blauen Donau/Schwimmt ein Krokodil (On the blue Danube/swims a crocodile) . . . ’

The paragraph breaks. “This was about the time that Neville Chamberlain paid his visit to Hitler in Munich.” Segal is a master at this, leading the reader one way and coming back around with a right cross. Other People’s Houses, first serialised in The New Yorker, bears an unintentional example of something Segal has spent much of her life since then mulling: the mutability of memory. She writes about arriving in England. “What I wrote,” she tells me, “is that I found myself alone on the top deck of the boat and I walked down the gangplank to a perfectly empty area and sat down and cried.” This was her memory. But the makers of Into the Arms of Strangers, an Oscar-winning documentary about the Kindertransport made in 2000 — in which Segal and her family appear — discovered a photograph of that moment: it shows a gangplank full of children. “And there I am, with this little thing identifying me . . . this little cardboard square on a shoestring around the neck,” she recalls. “So what happened? My memory is that I was totally alone, without my mommy or any grown-up . . .[but] the fact is I was surrounded [by other children]. So, when you ask me what happened, it’s such a complicated question. I can give you so many different answers. I can give you the real answer or I can give you the answer that was real to me.”

Segal’s work — five novels in 50 years, eight children’s books, a number of short stories and translations — all deal, in one way or another, with displacement. All are glosses on versions of Lore Segal: refugee, writer, thinker, human.

Before leaving Vienna, she recalls her father saying: “‘When you get to England, you have to ask the English people and get Mommy and me out and your grandparents and Aunt Whatshername and the twins, and you’ve got to talk to all the English people.’ From then on, I had it in my head that it was my job to get all these people out.”

And so she did. She saved her parents through writing: first a letter, composed at a processing camp on England’s eastern shore, that made its way to the UK Refugee Committee, which eventually found her parents domestic service visas — “proving that bad literature makes things happen”, as she writes in the preface to the re-released novel. Her second piece of writing was for her English foster parents, called “the Levines” in the book, who did not seem to understand the horrors of Hitler’s Europe. So she sketched it out in prose, in a notebook “with a white label with a red ring around it and filled the 36 pages, in German, with what had happened . . . Ruth, the youngest of the Levine daughters and my particular friend, got someone to translate it into English. It made Mrs Levine cry.”

Her parents arrived the next year. They ended up working as a cook-and-butler duo. But then her father was interned on the Isle of Man, along with other male “German-speaking aliens”. He suffered a series of strokes and died shortly before the war ended. Soon, her mother, grandmother and beloved Uncle Paul signed up for the visa quota to America, where opportunity awaited. In 1951, after three years in the Dominican Republic, they moved to New York.

Segal says her third novel, Her First American (1985), which took 18 years to write, is her best. “It has the best writing.” It is also deeply complex, honest and funny. It’s a sort of Bildungsroman about Segal’s American awakening via a love affair with a middle-aged, alcoholic, black intellectual named Carter Bayoux — based on the writer Horace R Cayton Jr — and her first glimpse of the reality of American racism. The real Segal arrived in New York on May 1 1951 and took up with Cayton not too long after (10 years later, she married David Segal, a literary editor with whom she had two children, Beatrice and Jacob.)

“It is autobiographical with all the liberty one gives oneself when one’s writing a novel: some things happened, some of them didn’t, but essentially it is that,” she says. “I think of it as myself learning to be an American through the lessons given me by an intellectual black man . . . How much better can you do than have that experience? Not only that, but he was enraged, he was damaged, and he was ironic. When you put that together, you really got in. I don’t know anybody who had the good luck to fall into that, to have that experience.”

In the middle of writing the novel, Segal took a three-year break to write Lucinella, a sort of magical-realist romp about a young writer’s life among New York’s literati. “It was a lark . . . I had a good time — anything goes,” she says. “I re-read it the other day for the first time in 40 years, and I thought, ‘My goodness, I had a lot of ideas.’”

Putting them down on paper has never been a problem for Segal. “I am a good writer. There’s always the grief that one isn’t Shakespeare, and it’s a real grief. If I’m not Shakespeare, the hell with it,” she says. “The reason we do what we do is because we know how to do it. We’ve learnt how to be good at it, whether it’s a sport or an art, or being a marvellous cook, or being a marvellous mommy or whatever it is that we are good at. It’s what we enjoy, I think. There’s a pleasure in getting a sentence right, and it may take a week or so, or a month or a year or so.”

She still follows the same writing routine that Cayton helped her develop decades ago. Up at about 6am, eat breakfast and then start writing at about 7am or 8am. “And then I sit there, till one o’clock, whether anything comes of it or not, seven days a week,” she says. “And I keep wondering, what do people do who don’t write from eight o’clock until one o’clock? What do they do with their hands? I would find it really hard to not do that, to stop right now. And it has been a blessing. I even asked my children, ‘Please, if you’re going to break your leg, do it in the afternoon because in the morning is when I write.’”

She used to write downstairs, in the ground floor apartment of her mother, whom she loved dearly. Franzi Groszmann died in 2005 at the age of 100. “I had the best mother in the world,” Segal says. She has written about her mother getting old, living in a nursing home. I wonder what she learnt while watching her mother age. “That it’s a bad idea. I learnt to know what a nursing home is like and that I didn’t ever want to be in one,” she says. But her mother was quite nice about the whole affair. “My mother said, ‘It’s very nice here. They’re very good to me here.’ I thought I had been a bad daughter because, of course, I could have [tried to care for her at home]. People manage. I did not think I could manage. And my mother said, ‘No, put me here.’ And then I visited her . . . almost every other day. And she told me I was a good daughter, which is gracious, certainly.”

Will she be gracious if her kids decide to put her in a home? “Never, never, never.” But her eyes twinkle. She knows her kids have a “loophole” — “they will know that you put your mother in a nursing home, so that if it happens, actually, they will not feel too bad.”

For obvious reasons, Segal’s recent work has been principally occupied with ageing. But she also thinks a lot about her own youth. “I say to young people, ‘Did you have a good childhood? Did you have a good [adolescence]?’ No! Because you don’t know how things work, you don’t know how to do things . . . In those days, we were keeping ourselves virginal. It was a bad idea. It was a bad deal,” she says. “We were all of us late bloomers because we didn’t know how, and the guys didn’t know how. And there weren’t any guys. What guys were there at the end of the war? I was living with two elderly old maids. I went to an all-girl school. I went to an all-girl college. And if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have known what to do anyway.”

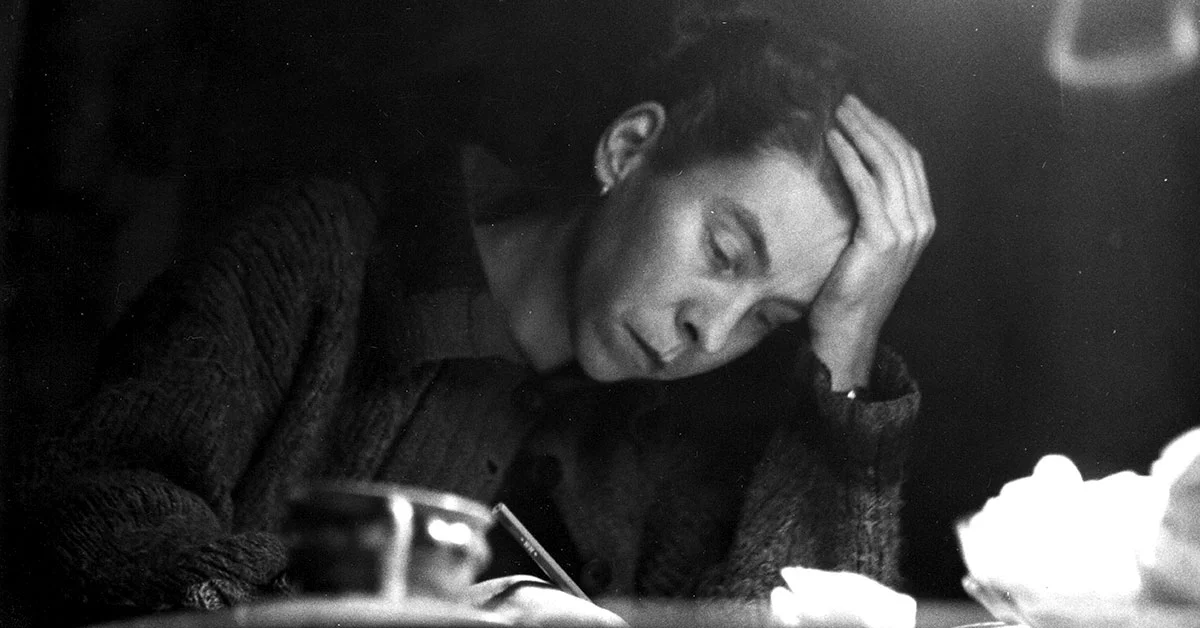

A thought occurs. “I want to show you what I looked like at 19, OK?” She asks the photographer to fetch a picture of her and a friend from her study. “The two of us in the garb of postwar England. Miserable-looking.”

There’s Segal. Frizzy hair, high forehead, glasses, a square skirt and a blouse with wide, flouncy lapels. Beaming and blurry in black and white. She makes the photographer swear not to use it. “You guys look so happy,” I say. “Oh my God. Oh my God. It’s the saddest looking thing,” she says. “To go through the world looking like that at 19?”

“You guys look beautiful!” I protest. She scoffs. It was that girl, a few years later in New York, who thought — against all the available evidence — that she had nothing to write about. Until one night at a party when someone asked her how she’d ended up in America. She began to tell her story, and pretty soon the entire room was rapt. “That was the moment when I realised I had stories to tell.”

I wonder what she’s learnt as she’s got older. “I don’t know. Do I know something I didn’t know before? I haven’t noticed.” The question makes her think of the day she left her parents in Vienna. “The other kids were howling and crying,” she says. But not Segal. “When you do that, you do disconnect from a depth of feeling that you can’t bear, and that becomes a way to manage it. I feel as if I’m a cheerful old person, but it’s perfectly possible that I’m playing that same game. Maybe I’m saying, ‘Oh, isn’t this interesting?’ Because I don’t want to know that I’m 90 and will be dead sooner or later. I don’t feel as if this is a big deal, but I’m not sure. I’m not sure that I’m [not] doing this number on myself at 90 that I did at 10, [thinking], ‘Isn’t this interesting?’, which is much easier to think about than ‘Isn’t this the abyss?’”

Besides a stint in Chicago, Segal has never lived more than a block from Riverside Drive on the Upper West Side since moving to the US. “That’s my America now, you see? In Riverside Drive, I’m at home. I understand this. I know where the lights turn on and where they keep the spoons and I know New York. I know how to talk in New York. I know where to go in New York.

“That’s where my roots went down. You know that wonderful word — I’ve been ‘naturalised’. I used to think, ‘Wait a moment, you mean before I came to America I wasn’t natural?’ It means to be made as if you had grown up there, and I feel very much like that about Riverside Drive. To have grown up somewhere, you begin with roots, right? Well, if you are naturalised, you have to make roots or roots are made for you . . . and I feel very much like that. I am totally comfortable in a very small part of the world, and it’s up and down Riverside Drive.”

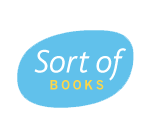

Neil Munshi is an FT reporter in New York. Lore Segal’s “Other People’s Houses” is republished this month by Sort of Books Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos